Knowing your food costs is critical for running a profitable restaurant. How can you set menu pricing without it? We’re talking exact costs—no rough estimates—because the numbers behind your recipes are just as important as the flavors.

But you’re a culinary professional, not an accountant. Let’s walk through how to calculate your true food cost, plus the cost of a recipe and a dish.

Why Standardized Recipes Matter for Accurate Food Costing

You cannot accurately cost a menu item that changes every service. Consistency comes from standardized recipes. A standard recipe is a “locked,” documented recipe with precise measurements and procedures. It ensures a dish comes out the same every service, regardless of kitchen staff.

Why use a standard recipe in your restaurant? Consider this: if one line cook serves an 8-ounce portion of mashed potatoes and another serves a 10-ounce portion, your plate cost can vary by 25%.

The moment you lock your recipe down, you gain control over your numbers—and you’ll be able to eliminate many of the hidden inaccuracies that distort and drive up food costs.

Did you know? Built for restaurants by restaurant pros, meez helps you enforce recipe standardization and avoid guesswork by calculating the true cost of ingredients.

As-Purchased (AP) vs. Edible Portion (EP) Cost Explained

The most important concept to understand when it comes to restaurant food costing is the difference between as-purchased cost and edible portion cost (i.e., AP cost vs. EP cost).

What Is As-Purchased (AP) Cost?

As-purchased cost, or AP cost, is the price you pay for ingredients in the form you purchase them. It’s what shows up on your invoices, e.g., $1.20 per pound of onions, $12.50 per pound of whole salmon, $2.50 per bunch of kale.

What Is Edible Portion (EP), or Ingredient Yield, Cost?

Edible portion cost, or EP cost, is the cost of the usable portion of food ingredients after trimming, peeling, cooking, or processing. It’s the cost for what ends up on the plate. This is also known as an ingredient yield.

For example, a whole salmon might cost $12.50 per pound AP. But after you remove the head, bones, and skin, you may only end up with 60% usable fillet. That means your EP cost per pound of salmon fillet is much higher than $12.50.

Why This Distinction Determines Your Profitability

You never get 100% yield from any ingredient. Bones, shells, moisture loss, and vegetable trimmings all add up. Calculating recipe costs based on AP cost can lead to menu pricing that doesn’t adequately cover food costs or generate a profit.

Pro chef tip: Running the math manually for every ingredient can be tedious. With meez, EP costs are automatically calculated for over 2,500 ingredients, saving you time and ensuring your numbers are always precise.

How To Use Yield Tests to Find Your True Food Costs

Before you can calculate the cost of a full recipe, you need to know your individual ingredients’ EP costs. Yield tests are the most accurate way to move from AP cost to EP cost. Yield testing is the practice of measuring how much usable product you get from an ingredient after processing it.

Calculate Food Costs Correctly: Step-By-Step Instructions

Use a yield test to find out your true ingredient cost in three steps:

1. Record AP and EP weights.

Weigh your ingredient in its AP form (aka AP weight or AP volume). Weigh again after processing to get the EP weight. Some chefs call this the Ready-to-Serve weight, or RTS weight.

2. Calculate yield percentage.

The formula for calculating yield percentage is:

(EP Weight ÷ AP Weight) × 100 = Yield %

3. Use yield percentage to calculate EP cost.

Once you know an ingredient’s yield, you can calculate the edible portion (EP) cost using the following formula:

EP Cost = AP Cost ÷ (Yield % x 100)

How to Yield Test Produce: Steps and Examples

Let’s say you buy a 5 lb. bag of yellow onions for $0.80. After peeling, trimming, and prepping, you’re left with 3.75 lbs. of usable onion. Use the steps above to calculate your EP cost.

Weight of yellow onions before and after prep: AP weight = 5, EP weight = 3.75

Yield percentage for yellow onions: 3.75 ÷ 5.0) × 100 = 0.75 x 100 = 75% yield

EP cost for yellow onions:$1.07 per pound

Your EP cost per pound for yellow onions is significantly higher than the AP cost, and this is just one vegetable example. Your true food cost can be much higher for some vegetables (e.g., those with only the leaves as the edible portion).

Yield Testing Protein: Conducting a Butchery Test

Yield tests for proteins are even more critical because of their higher cost and dramatic weight changes during prep and cooking. You’re removing trimmings, bones, and sometimes skin and other inedible pieces (think of a chicken or fish example).

Imagine purchasing a 10 lb. beef tenderloin for $14 per pound. After trimming fat and accounting for moisture loss during cooking, you may only have 6.5 lbs. of usable product—a 65% yield. That makes the EP cost of your trimmed tenderloin closer to $21.50 per pound.

Butchery tests also highlight opportunities for efficiency. Proper knife skills and trim utilization can reduce waste and increase profitability.

Did you know? In the meez platform, yield tests are built into the system. When you log your AP and EP weights, the platform automatically calculates yield percentages and updates your costs in real time. That means your recipe cards always reflect the true cost of what’s on the plate.

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Recipe Cost

Now that you understand how to use AP, EP, and yield tests to calculate your true food costs, let’s build a recipe. In just two steps, we’ll calculate the cost of a plate from its components.

Step 1: Cost Your Sub-Recipes

Batch recipes like stocks, sauces, and dressings are the backbone of most kitchens. But because they’re made in large volumes, it’s easy to overlook their per-portion costs.

To cost a sub-recipe, calculate the total ingredient cost, then divide by the yield to get the cost per unit (ounce, gram, liter, etc.). Here’s the formula:

Unit Cost = (Total Ingredient Cost) ÷ Yield

For example, if a 2-gallon batch of béchamel costs $24 to produce and yields 256 ounces:

$24 batch cost ÷ 256 oz yield = $0.09 per oz unit cost

Breaking down batch recipes into dollar value ensures your calculations are precise when those sub-recipes appear in multiple dishes. If your lasagna recipe calls for 60 ounces of béchamel, for instance, that adds $5.40 to your recipe cost. More on this in Step 2.

Did you know? With meez, you can link sub-recipes to parent recipes (e.g., béchamel to lasagna), so every portion automatically pulls the correct cost.

Step 2: Calculate Price Per Serving & Total Plate Cost

Once you’ve calculated the EP cost for each of your recipe’s components, you have everything you need to calculate the total plate cost. On your recipe card, include columns for each ingredient, as well as portion size and EP cost. Add up the EP costs of each ingredient to arrive at the total plate cost, or cost per serving.

From here, you can adjust pricing and calculate your food cost percentage and contribution margin to begin menu engineering work.

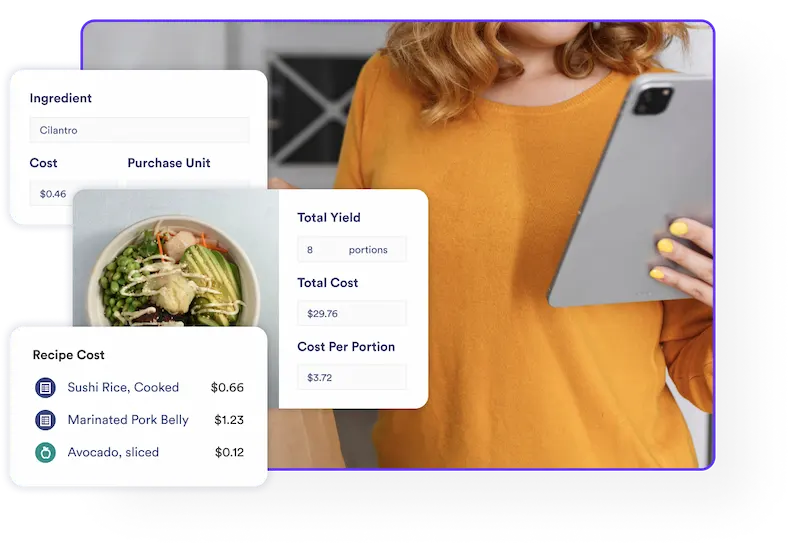

Within the meez platform, these calculations are displayed automatically, with recipe cards that update in real time when prices change. Instead of hunting through spreadsheets, you’ll always know your current plate cost.

Don’t Forget the Details: Accounting for Hidden Costs with the Q-Factor

Even the most thorough costing exercise misses some details. What about the salt and pepper? The parsley garnish? That drizzle of olive oil you use to sauté vegetables? These may seem negligible, but across hundreds of plates each week, they add up. That’s where the Q-Factor comes in.

What is a Q-Factor?

The Q-Factor, sometimes called the Spice Factor, is a percentage add-on that helps restaurants account for the cost of small, often overlooked ingredients. These can include spices, oils, garnishes, and basic condiments.

How to Calculate Your Restaurant’s Q-Factor

To figure out your Q-Factor, review invoices for items that aren’t tracked in recipes—the ingredients your kitchens add in tiny quantities. Then, calculate the total cost of those items as a percentage of your total food cost:

Q-Factor = (Total Cost of Spices, Oils, Garnishes, etc. ÷ Total Food Cost) x 100

Many restaurant operators find these add up to 1–5% of total food cost. For example, if your total food cost is $30,000 per month and your invoices show $1,200 spent on these untracked items, your Q-Factor is 4%.

Applying the Q-Factor to Your Final Plate Cost

To add your Q-Factor to your plate cost, take your total recipe cost and multiply it by the Q-Factor. If your plate cost is $4.94 and your Q-Factor is 4%, add $0.20.

Final Plate Cost = Total Recipe Cost x Q-Factor

Recipe Costing Tools: Spreadsheets vs. Culinary Operating Systems

Accurate recipe costing can be managed with spreadsheets, but manual methods come with major limitations.

The Recipe Costing Template: The Pros and Cons of Spreadsheets

A common misconception about custom recipe costing templates is that the spreadsheets they’re built in are flexible and accessible. But that’s only true if you have time for formula maintenance and version control, and if you enjoy programming and accounting.

Spreadsheets also require constant updates, and one mistake in a formula can throw off your entire menu analysis. Spreadsheets also don’t update automatically when ingredient prices change. With the pace of supplier fluctuations, this means you’re always playing catch-up.

The meez Advantage: Real-Time, Accurate, and Integrated Costing

Modern restaurant kitchens are moving beyond spreadsheets to digital platforms. With meez, your ingredient costs update automatically, yields are calculated instantly, and recipe cards are standardized across your team.

That means your plate costs are always accurate and your menu engineering decisions are based on real-time numbers. You spend less time playing accountant and more time doing what you love because your recipe costing system finally works.

Your Next Move: Turning Accurate Costs into Strategic Profit

For today’s restaurant, recipe costing is the foundation for controlling operating expenses and strategic menu design. Learn how to optimize menu offerings and set profitable pricing in The Ultimate Guide to Menu Engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions About Recipe Costing

How is per-dish food cost different from overall food cost percentage?

Per-dish food cost (also called plate cost) is a proactive calculation of the cost of all ingredients that go into a single menu item, calculated before the dish is sold. You use it to set prices and make menu engineering decisions. Overall food cost percentage is a reactive accounting metric that looks back over a set period, usually a week or a month. The standard formula is:

Overall FCP = (Beginning Inventory + Purchases – Ending Inventory) ÷ Total Food Sales

Both numbers are important, but they address different questions. Plate cost tells you what a dish should cost, while overall food cost percentage tells you how your kitchen actually performed.

What is the restaurant food cost percentage formula for a single dish?

The formula for food cost percentage for a single dish is:

FCP = (Total Plate Cost ÷ Menu Price) × 100

For example, if a dish costs $4.50 to prepare and sells for $18.00, the food cost percentage is 25%. Tracking this number helps you identify whether your dishes are priced to hit your profit goals.

How do I determine my ideal food cost?

Your ideal food cost is a target your restaurant aims for to meet profitability goals. Learn how to set your ideal food cost target in our guide to actual vs. theoretical food costs.

How do I account for supplier price fluctuations in my recipe costs?

Ingredient prices change constantly, especially for proteins, produce, and other commodities. If you’re using spreadsheets, you’ll need to update your ingredient prices manually and re-run the calculations. Many chefs now use platforms like meez, which update ingredient prices in real time. That way, your recipe cards always reflect current costs without hours of manual work.

How often should I re-cost my entire menu?

At a minimum, reviewing recipe costs seasonally or whenever you change dishes. But if supplier prices shift frequently in your market, re-costing quarterly—or even monthly—will help protect your margins. With meez, re-costing happens automatically in the background, so your numbers stay current without interrupting service.